No matter what level of sport you or your children are involved in, you have likely known someone who has sustained a serious knee injury. Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries are probably at the top of the list for the most discussed. It is universally known as a season-ending injury, and is sure to draw some sympathetic looks from teammates. In the United States, approximately 120 000 people per year sustain an ACL injury. The numbers per year are increasing, and are higher in females when same-sport comparisons are made1. With the soccer season starting up, this seemed like the perfect time for a discussion.

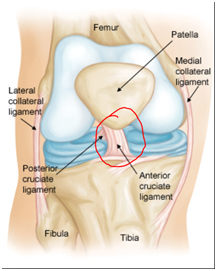

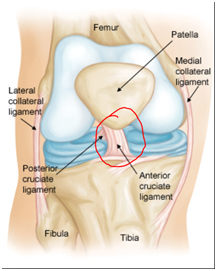

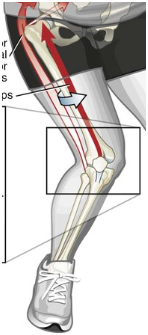

To understand the impact of an ACL injury, it is important to know what the ACL is. It is a ligament that runs between the tibia and femur. It is considered to be a primary stabilizer against forward movement of the tibia on the femur, but also helps to resist valgus forces (see below), limit rotation and facilitate normal joint mechanics. Although it plays a big role in the above, there are also other structures that help out, which explains why some people can still operate in a semi-normal fashion despite an ACL injury.

A. Anterior view of the knee, ACL highlighted in red

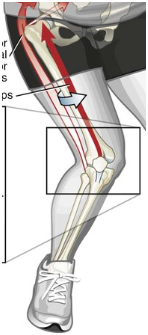

So how do these injuries happen? Often they are non-contact injuries2. Examples include sudden deceleration from a sprint, forceful rotation, landing from a jump, valgus positioning and knee hyperextension (although this is debated). Depending on the sport, they can also be contact injuries. Signs and symptoms of an ACL injury include hearing a “pop”, a quick onset of swelling, difficulty weight-bearing, and feeling unstable1.

B. Example of a valgus knee injury, which happens when the knee collapses toward the other knee

Luckily, it is possible to predict if you are at risk for this type of injury. Below is a list of risk factors for ACL injury supported by research3,4. It should be noted that a great deal if this research focuses on the female athlete.

- Being female: Due to anatomical and hormonal differences.

- Increased joint laxity

- Excessive hamstring laxity: This allows more forward translation of the tibia and stresses the ACL.

- Insufficient ratio of hamstring to quadricep strength: If quads overpower the hamstrings, the tibia is pulled forward.

- Poor lower extremity control: Difficulty controlling knee position during dynamic movements.

- Impaired proprioception: This means poor joint position sense, or difficulty determining what position the knee is in.

- Being overweight

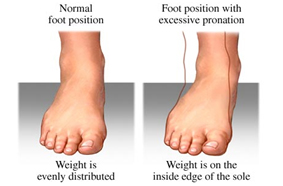

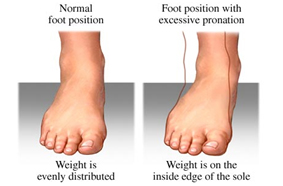

- Excessive forefoot pronation: While pronation (foot flattening) is a necessary movement for walking and running, if it occurs excessively or too quickly, it can increase the risk of ACL injury.

Despite the long list of risk factors, prevention is possible, and strategies aimed at this are effective. Early physiotherapy intervention can help to identify and generate solutions for individual risk factors. Neuromuscular training programs are a great way to protect against these injuries5,6. In simple terms, this means performing strengthening, coordination, balance and other types of exercises to improve strength or relevant muscles and simulate situations in which an athlete may become injured. These programs have actually demonstrated measurable changes in movement patterns5,6 and have been shown to reduce ACL injury rates by approximately 50%7. A great example of this is found in the FIFA 11+ warm-up, which when utilized in elite collegiate soccer programs, helped to reduced overall injury risk by more than 40%8. An easy google search will bring up photos and videos of the exercises.

It is possible that those of you reading this will have one or more of these risk factors. However, some may be more obvious than others. For best results, consult a physiotherapist for advice on injury prevention.

Article provided by Registered Physiotherapist, Nick Peters. Nick believes in an eclectic approach to treatment, with an emphasis on manual therapy, dry needling and functional and sport-specific exercise. Appointments with Nick can be made at the Athlete's Care Hamilton location.

References

1. Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. Clinics in Sports Medicine (2017).

2.Collegiate ACL Injury Rates Across 15 Sports: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System Data Update (2004-2005 Through 2012-2013). Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine (2016).

3. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Female Athletes-Part 1: Mechanisms and Risk Factors. American Journal of Sports Medicine (2006).

4. High knee abduction moments are common risk factors for patellofemoral pain (PFP) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in girls: Is PFP itself a predictor for subsequent ACL injury? British Journal of Sports Medicine (2015).

5. Effects of evidence-based prevention training on neuromuscular and biomechanical risk factors for ACL injury in adolescent female athletes: a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine (2015).

6. Comparative Adaptations of Lower Limb Biomechanics During Unilateral and Bilateral Landings After Different Neuromuscular-Based ACL Injury Prevention Protocols. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (2014).

7. Interventions Designed to Prevent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Adolescents and Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. American Journal of Sports Medicine (2012).

8. Efficacy of the FIFA 11+ Injury Prevention Program in the Collegiate Male Soccer Player. American Journal of Sports Medicine (2015).